Virtual Water Trade: Economic Solution towards Agriculture-led Water Scarcity

As I suggested in my last post, building reservoirs or other forms of water storage facilities could aid in adjusting seasonal imbalances of water resource allocation. Following that, let's talk about another creative solution to the uneven spatial distribution of water.

Virtual Water: The Theory

Since its inception in the early 1990s, the virtual water trade has grown in popularity as a special solution to national water scarcity. The term "virtual water" relates to the water required to manufacture certain agricultural products (sometimes also further applies to water used in non-agriculture items). This proposal came up with a technique for countries to compensate for their water shortages through economic processes. Instead of producing water-intensive commodities in-house, countries could choose to import them and spare their limited water resources for domestic consumption. On the other hand, water-rich nations can also benefit from their surplus water resource by exporting water-intensive products.

As stated by Allan, "virtual water is a term that links water, food and trade" (2003, p.6). Such a notion offers up new ways of thinking to address physical water scarcity from an economic standpoint. In principle, a positive net virtual water import balance may remedy a water deficit, but the reality is far more complicated. Using virtual water trade as a major comfort of water shortage requires a move away from national food self-sufficiency. Excessive agricultural export prohibitions may also threaten local farming livelihoods as well as national economic prosperity. Water policymakers may face high political risks when overly relying on virtual water trade.

Virtual Water Trade in Kenya: A Case Study

Located in the east coast of Africa, Kenya is one of the largest exporters of virtual water in the Nile Basin. Its tea and coffee exports, together with Uganda's, account for the majority of virtual water flow within the basin (Zeitoun et al., 2010). Exporting farming consumes a substantial amount of water in Kenya. As indicated by Mekonnen & Hoekstra (2014), export products accounted for 23% of the agricultural water footprint in the nation from 1996 to 2005, which was about 4.1 km3/year. The majority of Kenyan agriculture is rainfed, hence croplands are concentrated in areas with more consistent rainfall, such as the Lake Victoria basin and the narrow coastal strip.

Kenya also imports crop products such as

cereals from neighbouring countries, which include around 4.0 km3 of

virtual water per year. As a result, the net effect of virtual water trade in

the country is more or less neutral (see also in Figure 1). However, current

renewable water resources are thought to be insufficient to satisfy Kenya's

water demands (Wong et al., 2005). The country could be classified as water-stressed

and in regions like the Lake Naivasha, and commercial farms have been criticised

for causing a reduction in lake level as well as fertiliser pollution in areas

such as Lake Naivasha (Mekonnen et al., 2012). Thus, although virtual water

trade currently has little impacts on Kenya's water security (Zeitoun et al.,2010), it could be a potential method to adjust the country's national water deficit.

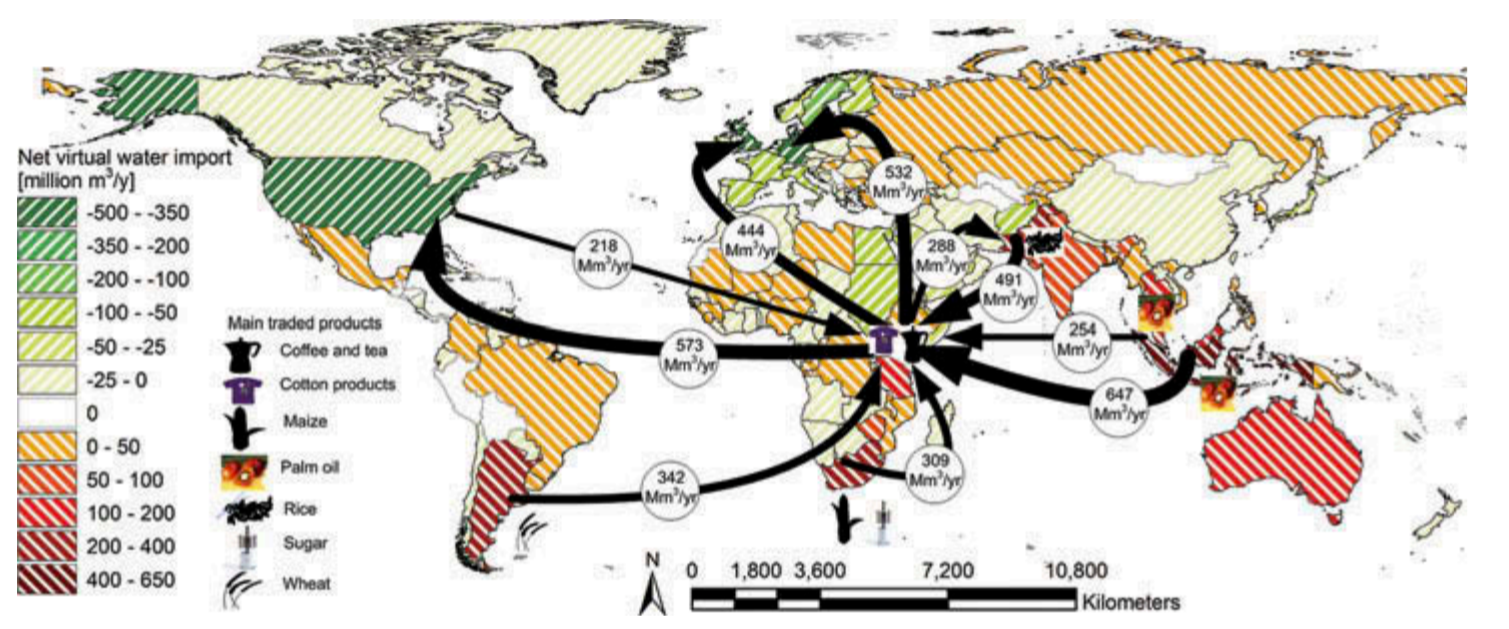

Figure 1: Countries with a positive (green)

or negative (red) net virtual water balance with Kenya. Black arrows indicate

the greatest virtual water flows into and out of Kenya. Source: Mekonnen & Heokstra, 2014.

Whereas it would be unwise for Kenya to impose severe restrictions on agricultural exports in order to create a positive a positive net virtual water import balance. Kenya's present virtual water export is mostly centred on high-value products like coffee and tea, which produce a better return per unit of water consumed than the cereal crops Kenya import. Key exporting agriculture products plays a vital role in the nation’s socio-economic growth, as tea and coffee farming employ a considerable section of the people, both directly and indirectly (Mekonnen & Hoekstra, 2014). Reducing agricultural water use by improving irrigation efficiency and agriculture productivity while only exporting commodities with a high comparative economic advantage might be a smarter step forward in coping with water shortage using virtual water.

Hi Leshi, I really enjoyed reading your blog on virtual water trade with a specific focus on Kenya. For the concept of virtual water trade, how would you suggest for land-locked countries to approach this strategy where there is natural geographic barriers towards trade?

回复删除Hi and thank you for your comment Sihan! My opinion is that land-locked countries should weigh the advantages and disadvantages of creating ways to overcome their physical barriers. If long-term benefits exceed the short-term economic input, then maybe it's time for them to link themselves to the others with greater advantage in production! Also, virtual water trade should not just be international, it can also be conducted within the nation. (I didn't mention this point in the post, thank you for inspiring me!) Moving water-intensive sectors to more water available regions can also be an effective way to ease the water pressure in relatively water scared areas.

删除